| March 2017 | |||||||||||

| Top stories | |||||||||||

| In the news | |||||||||||

| Photos | |||||||||||

| Contact us | |||||||||||

| Archive | |||||||||||

|

States consider newborn screening cut-off values |

March 30, 2017 --

Newborn screening is the practice of screening every baby in their first 24-48 hours of life for certain harmful or potentially fatal conditions that are not otherwise apparent at birth. For babies who have abnormal screens for one of these conditions, rapid identification and treatment makes the difference between health and disability – or even life and death. Every year, more than 12,000 newborn lives are saved or improved through newborn screening. It is the largest and most successful health promotion and disease prevention system in the country.

A screening test looks for abnormal levels that may indicate signs of a disease when no symptoms are present. It tells a patient their risk – normal levels indicate low-risk and abnormal levels indicate high-risk. A diagnostic test determines if, in fact, the disease is present allowing the health care provider to make a definitive diagnosis and initiate treatment.

Newborn screening is not a diagnostic test but rather a screening test. It determines whether a baby has a high or low risk of having an illness or condition. If a baby has abnormal screening results, the baby’s levels are out of normal range. This immediately cues the health care provider to pursue additional diagnostic testing to determine if the baby has the illness or condition in question.

If a baby has symptoms or family history of a disease, parents should not rely entirely on newborn screening to rule it out, according to the Association of Public Health Laboratories. Health care providers should be consulted for additional diagnostic testing.

How are cut-off values determined and why do they vary from state to state?Every state newborn screening laboratory determines the optimal cut-off values for its population. The values are set using a number of factors and considerations such as:

- The disease’s prevalence and severity in the state’s population

- Race and ethnic differences in the state (relating to a disease’s prevalence)

- Environmental factors in the state (temperature or altitude, for example) that can affect testing

- Differences in the way the laboratory test is performed (methodology)

- Other factors unique to the laboratory and its equipment

For these reasons, a value in one state newborn screening lab cannot simply be compared to a value in another lab. The value associated with a normal screen in one state’s population may differ significantly from the value associated with a normal screening at another lab. That is, the line between normal and abnormal could be different in each state.

For example, Baby A gets a value of 14 which is normal in her state where the cut-off is 16. In a neighboring state, the cut-off is 10 so a 14 would be considered abnormal. However, because of differences in how cut-off values were determined and how the test was performed, Baby A’s sample would have screened at 8 in the neighboring state and been considered normal as well.

What are false positives and false negatives?Sometimes newborn screening will show that a baby has abnormal levels of markers for a disease, but further diagnostic testing is negative. This is a false positive. In extremely rare cases, newborn screening will show normal levels of markers in babies who will eventually develop diseases. This is a false negative or delayed diagnosis.

False positives can be extremely stressful for families. In some cases, the diagnostic process can take several months leading to distress and hardship for the baby and family. False negatives, on the other hand, mean that a baby might begin experiencing symptoms of a condition before being diagnosed. Depending on the condition, these symptoms could cause life-long development delays, permanent disability or even death.

If cut-off values are thought of as a filter, state newborn screening programs work to find the optimal filter to identify as many affected babies as they can. That may mean identifying more babies who are ultimately determined to be healthy in order to avoid missing others who may later receive positive diagnoses.

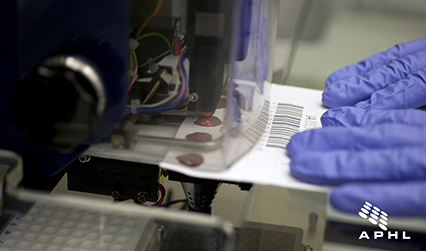

A Newborn Screening technician uses a single-hole punch to prepare blood spot samples for laboratory screening at the State Hygienic Laboratory.

A Newborn Screening technician uses a single-hole punch to prepare blood spot samples for laboratory screening at the State Hygienic Laboratory. While delayed diagnoses (also known as false negatives or missed cases) are extremely rare, they do happen. State newborn screening program staff work to save the lives of babies. They take this job extremely seriously. It takes just one delayed diagnosis reported to a newborn screening program to trigger a comprehensive examination of the system. Every effort is made to understand why the case was missed and what, if any, changes can be made to prevent additional delayed diagnoses.

When a delayed diagnosis is reported to the state newborn screening program, the laboratory scientists begin repeating the test to see if they get different results. They retest the baby’s bloodspot if it is still available and revalidate the testing equipment to make sure it is functioning properly. If everything is still the same upon retesting, newborn screening laboratory scientists will reevaluate the state cut-off values for the condition, consider altering the sensitivity of the testing equipment and/or determine whether the baby’s biology (fluctuating hormone levels, for example) may have affected the screen.

What has been done to prevent delayed diagnoses? Is there more that can be done?Many states have implemented processes to prevent delayed diagnoses while keeping false positives to a minimum. In most states, when a baby’s newborn screening results are abnormal, the test is performed again to confirm that the results are consistent. In cases where the value is abnormal but is close to the cut-off, second tier testing may be used. Second tier testing uses a more sensitive test that can eliminate some false positives and delayed diagnoses. But second tier tests are also more expensive, more complex and take more time than the primary method of testing. For these reasons, they are reserved for supporting or refuting a borderline abnormal result.

Additionally, newborn screening short-term follow-up staff review reports from clinicians of babies’ final diagnoses. This information, even if consistent with the baby’s newborn screening results, helps the program continue to improve the quality of the testing.